Building Solidarity Along the Entirety of Line 5

[Note: this essay is part of a series of six essays on How to Know about Line 5. You can read the series introduction and find links to the other essays as they are posted here.]

As someone who has just newly enlisted in the movement to help save the environment and people around me, I had trouble deciding how I wanted to best utilize my skills to make a difference. Thanks to the organization Oil & Water Don’t Mix, as well as the prompt emails of Bill Latka and Sean McBrearty, I learned that the Michigan Public Service Commission scheduled a meeting earlier this month, to discuss Enbridge’s proposed Line 5 tunnel. I attended the meeting and was made aware that the MPSC Staff recommended approval of Enbridge’s scheme.

Yes, that is correct. The MPSC Staff has endorsed the tunnel, notwithstanding the facts and studies that indicate continuing to keep a pipeline in the straits of the Great Lakes magnifies the risk of polluting 20% of the entire world’s freshwater supply, threatening the health and safety of humans and non-humans alike. Furthermore, constructing this tunnel will force continuing use of the pipeline for oil and gas transport and consumption for decades to come, despite the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels in order to curb global warming. The US Army Corps of Engineers has not yet released its study of the potential environmental impacts the construction of the tunnel will cause, but spoiler alert: the cement industry generates 8 percent of global carbon emissions (triple that of the entire aviation industry!). In addition, the construction process will cause massive disturbance to the lakebed and is sure to produce mishaps. Enbridge’s horizontal drilling in Minnesota, for example, caused 28 drilling fluid spills in one summer. And if all that isn’t bad enough, continuing operation of Line 5 also violates treaties with indigenous peoples. Yet despite all these factors, Enbridge and MPSC staff are still advocating for the tunnel.

I am angry, and I am fearful. Life, human and nonhuman alike, should not be commodified. Yet the fossil fuel industry, and the petroculture that Enbridge seeks to perpetuate, treats lives as nothing more than resources to be used to gain profit. But at what cost?

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Line 5 threatens more than just the Great Lakes[/perfectpullquote]

In making their determination in favor of the tunnel, the MPSC Staff treats Line 5 as a closed system, observing the proposition through the narrowest lens. Talks of risk to the Straits of Mackinac are rejected out of hand because the pipeline operates under the maximum pressure, yet nearly every other factor that is relevant (such as how old Line 5 is) is not examined sufficiently. It is easy to dismiss a (mostly unseen) pipeline, especially one that is remotely located under two of the Great Lakes. However, this pipeline is part of a complex and interconnected system, and the various areas it traverses and affects should no longer be ignored. The fact is, Line 5 threatens more than just the Great Lakes; it harms communities at the other end of the line as well. Consider, for example, the Black community in Detroit.

How is Detroit, of all cities, connected in any way to Line 5 and the Straits of Mackinac? The answer is simple. Enbridge pipelines provide feedstock to the Marathon Petroleum Company refineries in Detroit. Most of the product Marathon receives comes from the infamous pipeline Line 6B, now known as Line 78, which spilled into the Kalamazoo River in 2010. However, a portion of Marathon’s feedstock is diverted from Line 5 at Marysville, just before the pipeline crosses the St. Clair River into Canada, and is carried by the Sunoco pipeline to Detroit. So Enbridge supplies the product that leads to what is often called Michigan’s most polluted zip code, as two of Marathon’s three processing facilities are located specifically in the zip code of 48217. This zip code is important; despite only encompassing a two mile area, it includes communities such as Oakwood Heights and Boynton, and houses over 8,000 residents. Its inhabitants have expressed frustration with the actions exhibited by the industrial sector, “consider[ing] themselves a sacrifice zone, because many of the people that live [there] are Black low-income folk.”

In fact, these residents are victims of longstanding and ongoing environmental injustice in Detroit. But that injustice is part of a larger and longer history of racial discrimination in the US that contributes to residents’ living conditions. The demographics of 48217 are the result of racial discrimination through districting, an early twentieth-century practice known as redlining. Redlining, to be concise, was a tool that enabled the federal government to evaluate the riskiness of mortgages in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The government overwhelmingly rated neighborhoods where Black residents lived poorly, effecting a refusal to insure mortgages. This practice pushed many African Americans out of the suburbs and into urban housing projects. Redlining occurred in Detroit on June 1st, 1939.

While the official practice of redlining ended with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, other forms of housing discrimination persist. Marathon’s actions over the past two decades have extended the history of environmental injustice in Detroit. Back in 2008, when the company sought to expand, they started by buying up homes in Oakwood Heights to create a 100-acre green buffer zone. Oakwood Heights is 90% white (and Hispanic), while only 10% Black. Boynton, an adjacent neighborhood, is at least 71% Black, and only 10 homes from this area were purchased. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers Boynton a community without reinvestment potential, owing to the unusually elevated rates of and deaths from cancer. It is unclear whether or not anyone at Marathon knows that a correlation exists between proximity of air/soil/water pollution and cancer rates. At the very least, creating a buffer zone for Boynton would probably allow for reinvestment potential in the future, as well as ensure the safety of the current residents through healthier air, water, and soil. As it stands, the estimated value for most houses in Boynton is less than $15,000 and dropping steadily. Because the Black community that resides in Detroit are disproportionately the victims of these practices, they inordinately take the brunt of the ills produced by the activities of companies like Enbridge and Marathon.

There is no respite from constant reminders of this situation, either. Quotidian life for the residents of Detroit is dominated by sights and smells and sounds from Marathon. Theresa Landrum, a resident, spokesperson, and advocate for the people of Detroit, specifically takes issue with the encroachment of the refineries around residential areas, noting how “you could walk right from your house– front porch or back porch and walk right onto industries’ property.” The menacing presence of industry physically and mentally affects those who live there. The Kemeny rec center, for instance, is shadowed by the looming figure of the Marathon refinery, an inescapable and unwanted pillar of the Detroit community. And as if these towering giants weren’t bad enough, there have been many incidents throughout the years that explicitly threaten the safety of the citizens, from the explosion at the Marathon refinery in 2013, to the mountains of carbon-sulfur-selenium-vanadium chunks (otherwise known as pet coke) stored near the banks of the Detroit river, to the issues with flares compounded by the polar vortex in 2019.

The outdated racial districting processes that formed present day-Detroit have had long-term consequences that are compounded by companies cutting corners to increase profit margins, directly contributing to injuries to the Black community. In 2017, the NAACP discovered that 2,402 Black children have asthma attacks due to natural gas pollution, and miss 1,751 days of school as a result. Marathon, in punishment for their frequent and flagrant violations of regulations, installed an air system at a single school in Detroit. Every little bit helps, of course, except when you consider that these 185 students may be breathing in clean air for less than a quarter of their lives. Or when you consider that there are over 53,000 students attending public schools in Detroit that are breathing unclean air every second. As for adults, it doesn’t get easier for them to breathe; statistics indicate that, as of 2019, the rate of hospitalizations for Black residents in Detroit was more than three times that of white people. I mean, let the facts speak for themselves: nearly 80% of the population in Detroit is Black, and the asthma levels in Detroit were 46% higher than the entire state of Michigan!

Asthma is not the only source of fear for the people of Detroit. Lead studies conducted by the state of Michigan also reveal that the highest proportion of children with elevated levels of lead in their blood all originated from Detroit’s Wayne County. These levels as declared by the state of Michigan are so high, they warrant immediate action, according to the scale developed by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Further testing conducted in the soil around schools and parks have also revealed dangerous levels of lead and arsenic. Just as Line 5 is par of a complex and interconnected system, so too is health and biological safety influenced by many factors; the high concentration of heavy metals in turn combine to have a more toxic cumulative effect that hastens the deterioration of vital systems of the body. [perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]There is no reason anyone should be subjected to these living conditions.[/perfectpullquote]

Other chemicals also pervade Detroit, like sewer gas, which is a mix of chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide. Hydrogen cyanide, a byproduct of processing crude oil and a component of vehicle exhaust, can also be found in large amounts. Exposure to the chemical can cause headaches, nausea, issues with breathing, and chest pain. PFAS, chemicals that come from plastics and much more, has been found overflowing from a manhole next to Schaefer Highway, which leads to the Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA) Wastewater Treatment Plant. After investigation, Marathon was identified as a source of PFAS contamination. Additionally, PFAS has also been discovered in the soil and groundwater where the Gordie Howe Bridge is being built.

There is no reason anyone should be subjected to these living conditions. And while Enbridge is not solely responsible or producing those conditions, its Line 5 exists within a larger set of structures that need to be dismantled or overhauled to properly rectify the larger injustices that are presently occurring. By shutting down Line 5, we can begin to safeguard the health of our communities and take steps to address the inequities and inequalities that afflict Detroit.

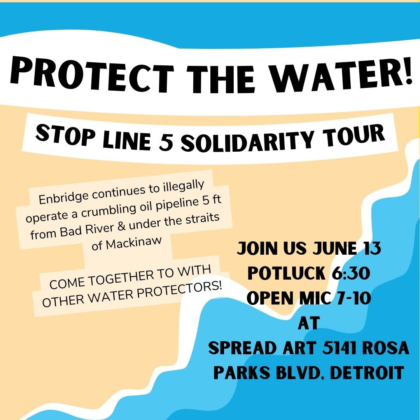

We must look towards solutions that are founded upon embracing a community and forging new relationships based on trust. The general public needs to be united to effect such large change. Building solidarity along the entirety of Line 5, linking those seeking to protect the Great Lakes to those dedicated to resolving urban pollution and environmental injustice, is a surefire way to ascertain everyone’s needs are met. This work is already beginning to take place; Oil and Water Don’t Mix hosted a solidarity tour community pop-up open mic night in Detroit on June 13th of this year (special shoutout to Detroit coordinator of Oil & Water Don’t Mix Hadassah GreenSky and the other attendees of the event). Everyone has stories and thoughts to share; we just need to listen. After all, don’t we all just want to make the world a better place?

We must look towards solutions that are founded upon embracing a community and forging new relationships based on trust. The general public needs to be united to effect such large change. Building solidarity along the entirety of Line 5, linking those seeking to protect the Great Lakes to those dedicated to resolving urban pollution and environmental injustice, is a surefire way to ascertain everyone’s needs are met. This work is already beginning to take place; Oil and Water Don’t Mix hosted a solidarity tour community pop-up open mic night in Detroit on June 13th of this year (special shoutout to Detroit coordinator of Oil & Water Don’t Mix Hadassah GreenSky and the other attendees of the event). Everyone has stories and thoughts to share; we just need to listen. After all, don’t we all just want to make the world a better place?